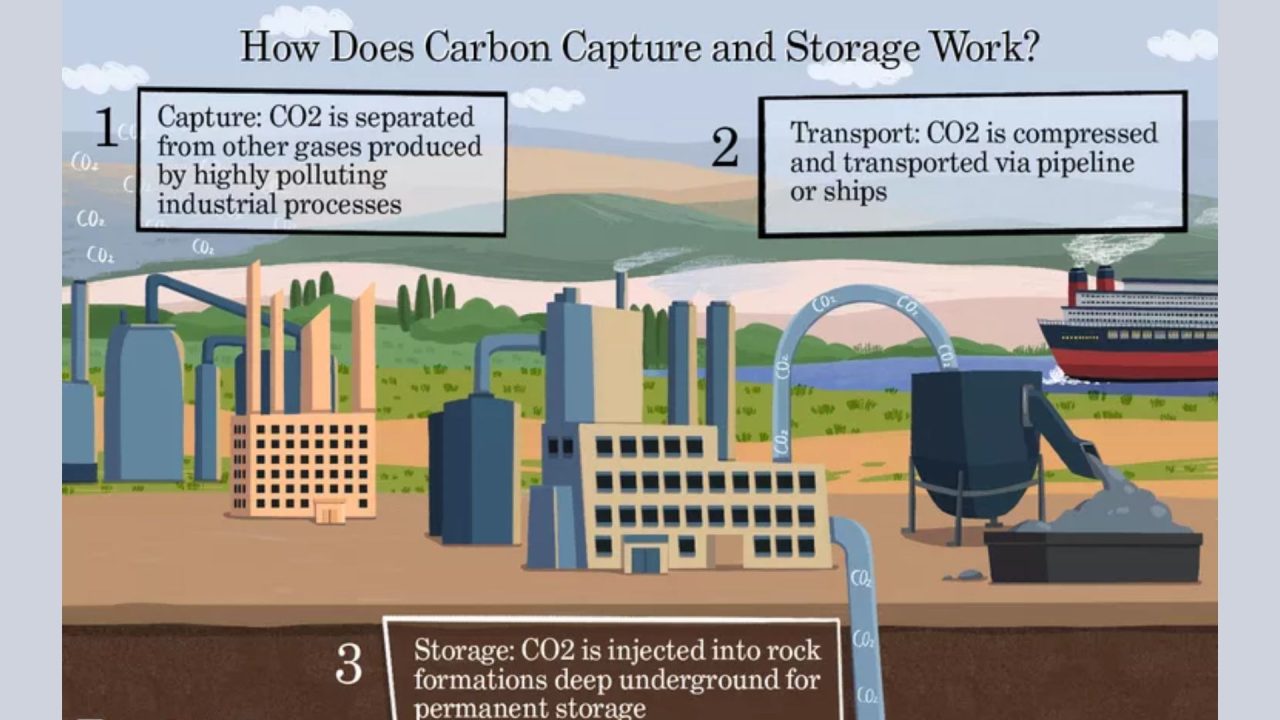

Norway’s government aims to demonstrate the feasibility of securely injecting and storing carbon waste beneath the seabed, asserting that the North Sea could soon serve as a “central storage camp” for polluting industries across Europe. Offshore carbon capture and storage (CCS) encompasses various technologies designed to capture carbon from high-emission activities, transport it to a storage site, and permanently sequester it beneath the seabed.

The oil and gas sector has long advocated for CCS as a potent tool in combating climate change, with polluting industries increasingly considering offshore carbon storage as a means to mitigate planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions.

However, critics have raised concerns about the enduring risks associated with storing carbon beneath the seabed, while activists argue that the technology poses “a new threat to the world’s oceans and a dangerous distraction from real progress on climate change.”

Norway’s Energy Minister, Terje Aasland, expressed optimism about his country’s “Longship” project, which he believes will establish a comprehensive, large-scale CCS value chain. “I think it will prove to the world that this technology is important and available,” Aasland remarked during a videoconference, alluding to the Longship project’s CCS facility in the coastal town of Brevik.

“I think the North Sea, where we can store CO2 permanently and safely, maybe a central storage camp for several industries and countries in Europe,” he added. Norway boasts a substantial track record in carbon management. For nearly three decades, it has captured and re-injected carbon from gas production into seabed formations on the Norwegian continental shelf.

The Sleipner and Snøhvit carbon management projects, operational since 1996 and 2008 respectively, serve as tangible examples of the technology’s feasibility. These facilities extract carbon from the produced gas, compress it, and transport it via pipelines for reinjection underground.

“We can see the increased interest in carbon capture storage as a solution, and those who are skeptical of such solutions can visit Norway and witness the success at Sleipner and Snøhvit,” remarked Norway’s Aasland. “It’s several thousand meters under the seabed, it’s safe, it’s permanent, and it’s an effective means of addressing climate emissions.”

Despite their successes, both the Sleipner and Snøhvit projects encountered initial challenges, including interruptions during carbon injection.

Citing these issues in a research note last year, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a U.S.-based think tank, suggested that rather than serving as flawless models for replication and expansion, these problems “raise doubts about the long-term technical and financial viability of reliable underground carbon storage.”

“Overwhelming” Interest

Norway is set to advance the $2.6 billion Longship project in two phases. The initial phase aims to establish a storage capacity of 1.5 million metric tons of carbon annually over a 25-year operational span, with carbon injections potentially commencing as early as next year. A potential second phase is anticipated to enhance the storage capacity to 5 million tons of carbon.

Advocates argue that even with the projected expansion in the amount of carbon stored beneath the seabed during the second phase, “it remains a drop in the proverbial bucket.” Indeed, it is estimated that the carbon injection would only constitute less than one-tenth of 1% of Europe’s carbon emissions from fossil fuels in 2021.

The government asserts that the construction of Longship is “progressing well,” although Minister Aasland acknowledged that the project has incurred substantial costs. “Every time we introduce new technologies to the market, it entails high costs. So, this being the first of its kind, the subsequent projects will be more economical and straightforward. We have gleaned valuable insights from this endeavor,” Aasland remarked.

“I believe this will prove to be a noteworthy project, demonstrating the feasibility of such endeavors,” he added. A pivotal aspect of Longship is the Northern Lights joint venture, a collaboration between Norway’s state-backed oil and gas giant Equinor, Britain’s Shell, and France’s TotalEnergies. The Northern Lights partnership will oversee the transportation and storage components of the Longship project.

Børre Jacobsen, managing director for the Northern Lights Joint Venture, disclosed that they had received “overwhelming” interest in the project.

“There’s a lengthy history of efforts to initiate CCS initiatives in Norway, culminating a few years ago in a concerted effort to draw lessons from past achievements — and less successful endeavors — to ascertain how we can effectively launch CCS initiatives,” Jacobsen conveyed to CNBC via videoconference.

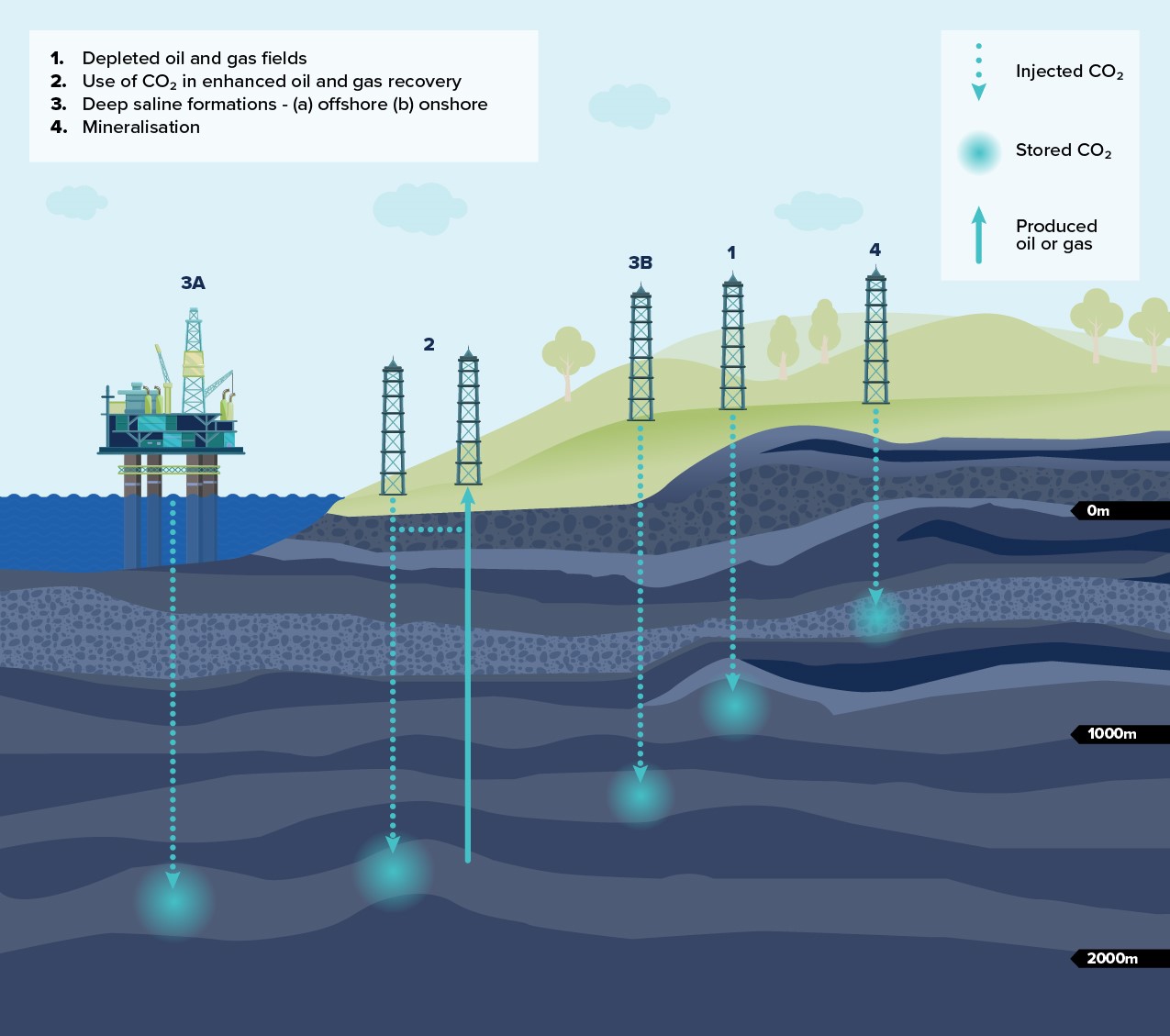

Jacobsen highlighted the North Sea as an exemplary illustration of a “vast basin” with considerable storage potential, noting the advantage of offshore CCS due to the absence of human habitation in those areas.

“There is definitely a public acceptance risk to storing CO2 onshore. The technical solutions are very solid so any risk of leakage from these reservoirs is very small and can be managed but I think public perception is making it challenging to do this onshore,” Jacobsen said. “And I think that is going to be the case to be honest which is why we are developing offshore storage,” he continued.

“Given the amount of CO2 that’s out there, I think it is very important that we recognize all potential storage. It shouldn’t matter, I think, where we store it. If the companies and the state that controls the area are OK with CO2 being stored on their continental shelves… it shouldn’t matter so much.”

Offshore carbon risks

A report published late last year by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), a Washington-based non-profit, found that offshore CCS is currently being pursued on an unprecedented scale. As of mid-2023, companies and governments around the world had announced plans to construct more than 50 new offshore CCS projects, according to CIEL.

If built and operated as proposed, these projects would represent a 200-fold increase in the amount of carbon injected under the seafloor each year. Nikki Reisch, director of the climate and energy program at CIEL, struck a somewhat cynical tone on the Norway proposition. “Norway’s interpretation of the concept of a circular economy seems to say ‘we can both produce your problem, with fossil fuels and solve it for you, with CCS,’” Reisch said.

“If you look closely under the hood at those projects, they’ve faced serious technical problems with the CO2 behaving in unanticipated ways. While they may not have had any reported leaks yet, there’s nothing to ensure that unpredictable behavior of the CO2 in a different location might not result in a rupture of the caprock or other release of the injected CO2.”